Wrocław, a city with a turbulent past and complex identity, hides within its streets numerous traces of bygone eras. One of the most intriguing—though not always appreciated—elements of its landscape are the bunkers: concrete relics of World War II that still remind us of the dramatic events of the 20th century. For some, they are fascinating objects of exploration and study; for others, they are silent symbols of dark times when humanity faced total war. Built to protect against destruction, today they themselves stand as decaying witnesses to history.

Wrocław as a Fortress – The Origins of the Bunkers

At the end of World War II, Wrocław—then the German city of Breslau—was transformed into Festung Breslau, a fortress meant to defend itself “to the last soldier.” This decision was made in 1944, when the war was already largely lost, but the German command hoped to delay the Soviet advance. As part of the preparations to this advance, the city saw the rapid construction and adaptation of numerous shelters, bunkers, and defensive fortifications strategically located throughout the area.

Many of these structures were built hastily, using both forced labor and local residents. Some of the bunkers were designed by renowned German engineers, including Richard Konwiarz, a noted architect of the interwar period who also created many of Wrocław’s public buildings. Thanks to his designs, air-raid shelters were built—several of which can still be seen today on Stalowa Street, Ołbińska Street, and near Strzegomski Square.

The Bunkers of Wrocław – Examples and Their Fates

The best-known and best-preserved structure is the bunker at Strzegomski Square, which now houses the Museum of Contemporary Art. This massive six-story reinforced concrete building—with walls up to two meters thick—was designed to accommodate hundreds of people during air raids. Its stark, windowless façade still commands respect and serves as a striking example of adapting a military building for cultural purposes. Inside, the museum preserves the structure’s original character: heavy steel doors, narrow corridors, and concrete walls evoke its wartime function.

Another notable example is the bunker on Stalowa Street, built in 1942 as an air-raid shelter for civilians. Though forgotten for decades, it has survived almost unchanged and is often visited by history enthusiasts and urban explorers.

There also existed a network of smaller shelters and tunnels beneath various parts of the city—from Nadodrze to Krzyki. Some were destroyed or buried during postwar reconstruction, while others served for years as storage rooms, coolers, or technical spaces. Wrocław’s underground still hides many secrets, and fragments of old defensive lines are occasionally uncovered during modern construction work.

From Fear to Fascination – Changing Attitudes Toward Bunkers

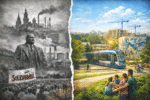

For many years, bunkers were regarded mainly as grim remnants of war—places that evoked suffering and destruction. During the communist era, little attention was paid to their preservation or documentation; some were demolished or simply left to decay. Only in recent decades has this attitude shifted, as people began to recognize their historical and architectural value.

Thanks to the efforts of local historians, enthusiasts, and organizations, the bunkers have started to gain a new life. The Museum of Contemporary Art is a model example of successful revitalization, showing how such sites can be transformed into spaces for creativity and reflection. Other bunkers have been adapted into galleries, exhibition halls, clubs, or art storage facilities. Historical walks and thematic tours devoted to Festung Breslau have also become increasingly popular, allowing participants to learn about both the military defense of the city and the everyday struggles of its inhabitants during the 1945 siege.

Meaning and Reflection

The bunkers of Wrocław are not only witnesses to the horrors of war but also symbols of endurance—of both the city and its people. Wrocław, almost completely destroyed in 1945, managed to rise from the ruins, just like these concrete structures that survived bombs, fires, and decades of neglect. Their continued presence reminds us of the importance of preserving historical memory and respecting the past, no matter how painful it may be.

Today, Wrocław increasingly views its bunkers not as relics of destruction but as part of its cultural heritage, worth studying, protecting, and creatively reusing. What once inspired fear now sparks curiosity and inspiration—for art, reflection, and dialogue about history.

The bunkers of Wrocław stand as monuments to difficult times that left an indelible mark on the city’s history. Although born out of war and devastation, today they serve as intriguing relics of troubled times—tangible reminders that connect the past with the present. Through them, we can understand how closely destruction and rebirth coexist, as do fear and curiosity, past and future. The bunkers of Wrocław are no longer just ruins; they are part of the city’s living memory, whose value grows with every generation.