Today, carnival brings to mind colorful parades, music, and carefree fun. Few people, however, remember that this tradition has a very long history, and its former face differed greatly from what we know now. In the Middle Ages—especially in such an important center as Poland’s former capital, Kraków—carnival, known as Zapusty, was a time of suspended everyday rules, culinary extravagance, street spectacles, and social role reversals. During this special period, city dwellers—from burghers to courtiers—allowed themselves joy and merriment before the coming, austere Lent.

Below, we’ll take a closer look at what medieval carnival in Kraków looked like: what customs accompanied it, what social role it played, and how it reflected everyday life in the city.

What Were Zapusty?

The word “Zapusty” referred to the final days before Ash Wednesday. It was the culmination of joy, feasting, and dancing, lasting from Epiphany until the last Tuesday before Lent. The Church viewed these festivities with some reservation, yet tolerated them as a natural “safety valve” before a time of penitence.

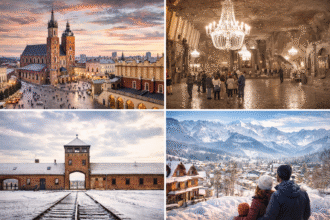

In Kraków, Zapusty were clearly visible in the streets—the market square and surrounding roads came alive, and residents donned colorful garments, masks, and costumes. Inspirations came from Italian and German traditions as well as local folk customs.

Feasts, Food, and Drink

One of the most important elements of medieval carnival was the abundance of food. Tables bent under the weight of meats, sausages, fish, roasted geese, and sweet pastries. During Zapusty, people liked to bake doughnuts—though they looked different from today’s and were often filled with… bacon fat.

In Poland’s former capital, feasts took place both at the royal court and in the homes of wealthy patricians. Meanwhile, in taverns and inns, craftsmen and apprentices celebrated. Feasting went hand in hand with music played on lutes, bagpipes, and pipes, while wine and beer flowed freely.

Spectacles and Role Reversals

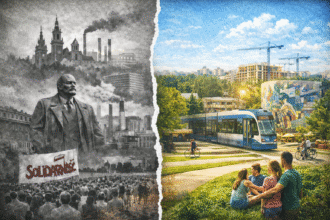

Carnival was a time when the world was turned upside down. The reversal of social roles allowed people to laugh—within limits—at authority figures. Popular parades included the “king of the shooters” or the “prince of fools,” who humorously imitated courtly ceremonies.

Jugglers, mimes, and wandering singers filled the streets. Masks and costumes offered a moment of anonymity, letting residents forget about hierarchy and everyday duties. In Kraków, jousting tournaments with a lighter, playful character were also organized, with knights appearing in fantastical outfits.

Festivities at Court and in the City

The royal court on Wawel Hill pulsed with life during this period. Balls, dances, and banquets were held for the country’s elite. Court musicians played dances in the rhythm of gavottes and basse-danse, and etiquette loosened somewhat compared to ordinary days.

In the city, folk celebrations reigned supreme: sleigh rides , carnival processions, effigies symbolizing the passing of winter, and even improvised theatrical performances. Craft guilds competed in organizing their own festivities, strengthening bonds within their communities.

Social and Religious Significance

Although carnival was a time of freedom, it also served an important social function. It released tensions, strengthened community ties, and symbolically marked the boundary between abundance and Lent. As soon as Zapusty ended, Lent took on even greater seriousness and spiritual weight.

In Poland’s former capital—where political, religious, and economic life converged—carnival also served as a stage showing the city’s power, wealth, culture, and diversity.

The medieval carnival in Poland’s former capital was more than just entertainment. It was a colorful spectacle of social life, blending folk traditions, courtly elegance, religious background, and the simple human need for joy. For a brief moment, social divisions faded, and people—regardless of origin—could enjoy being together, surrounded by music, dancing, and feasting. Although today’s carnival looks different, its spirit—joy, color, and laughter before a time of reflection—remains the same.