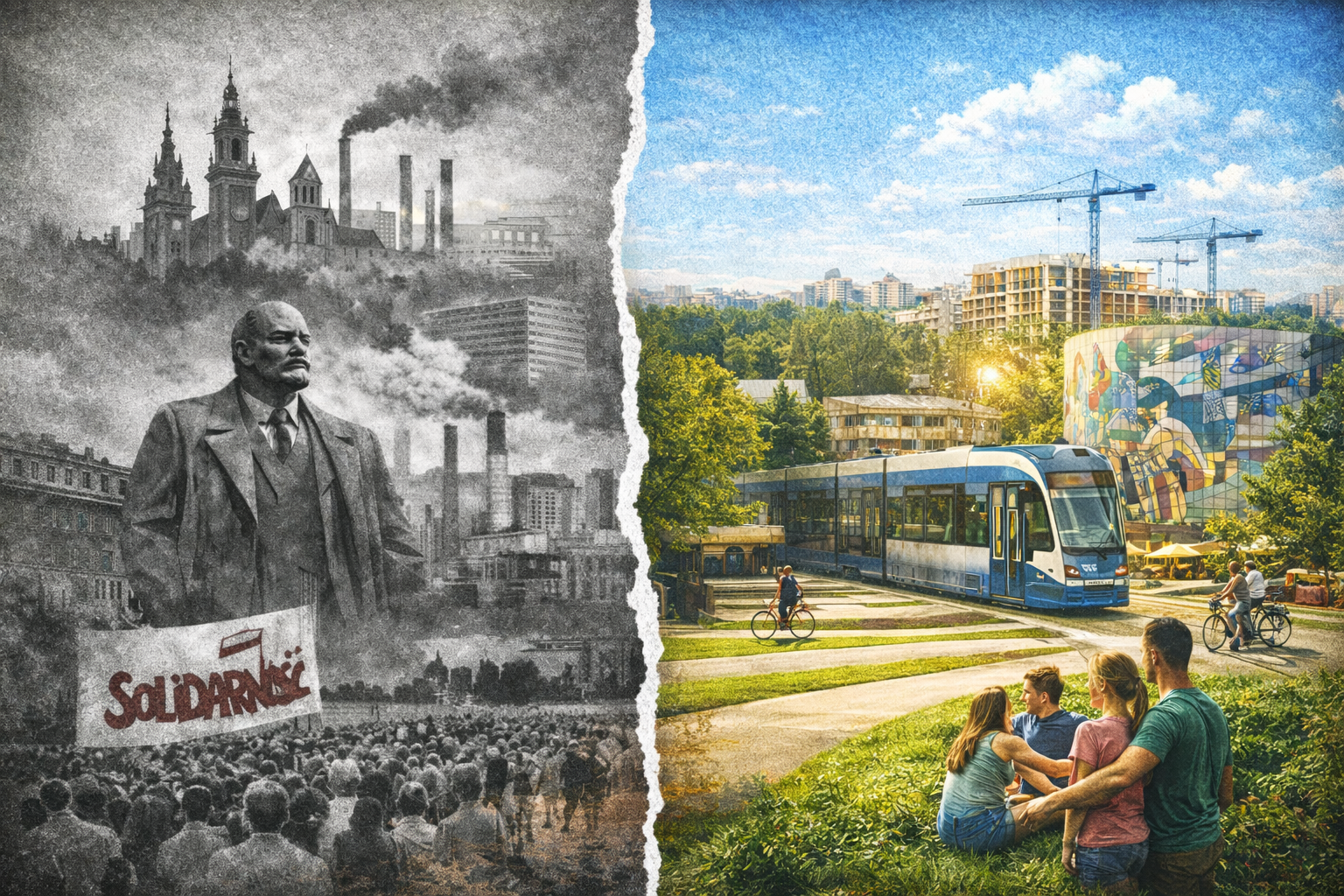

For decades, Nowa Huta has stirred strong emotions and continuously provoked debate. For some, it is a monumental relic of the communist era; for others, an inspiring laboratory of social, spatial, and cultural transformation. Built as an “ideal city,” it was meant to embody the vision of socialist modernity while serving as a counterweight to the intellectual and historic city of Kraków. Today, in an age of dynamic change, Nowa Huta is becoming a symbol of creative dialogue between past and future: a place where historical memory coexists with new forms of urban life, grassroots culture, and innovative urban projects.

Nowa Huta as an Ideological and Urban Project

The creation of Nowa Huta was an unprecedented event in post-war Poland. The decision to build a combined city–steelworks complex linked to the Lenin Steelworks (today ArcelorMittal Poland) was taken in the late 1940s. Nowa Huta was intended to be a model industrial center and a socialist utopia—a place where the worker would become the new hero of the collective imagination.

The city was planned according to the principles of socialist realism. Its space was organized around monumental visual axes, wide avenues, and central squares. The architecture was based on symmetry and impressive scale, while functionality was also emphasized: schools, cultural centers, cinemas, clinics, and green areas were integrated with residential buildings.

The apartments, although “modest,” offered a standard unattainable for many Poles in the post-war reality: bathrooms, central heating, and sewage systems.

At the same time, Nowa Huta was a profoundly political undertaking. Not only factories and housing estates were being built—new people were being created. Symbolic in this respect was the lack of churches in the original plans. The tension between imposed ideology and the needs of residents became one of the driving forces of later change.

The Community of Nowa Huta – From Pioneers to the Present

The first inhabitants of Nowa Huta came mainly from small and poor villages and towns near Kraków. New bonds were formed, and a fresh identity gradually emerged—not based on local tradition, but on the shared experience of building and working together. Over time, however, the housing estates began to develop their own rhythm, and residents started to build their own “small homeland.”

A particularly important moment in the history of Nowa Huta were the protests of the late 1960s and early 1970s, organized by residents seeking permission to build a church—today known throughout Poland as the “Lord’s Ark.” It became a material symbol of the faithful people’s resistance to communist ideology. In the difficult 1980s, during Martial Law, many inhabitants of Nowa Huta were members of anti-communist organizations and the famous Solidarity movement too.

Thus, a place created as a symbol of workers’ power became a space of social resistance. Paradoxically, it was in Nowa Huta that the conflict between official propaganda and real life became especially visible.

Today, the community of Nowa Huta is as diverse as the district itself. Alongside families who have lived here for generations, new residents are arriving: artists, students, and young families seeking more space and a calmer pace of life than in central Kraków. This diversity fosters the development of new social and cultural initiatives.

Nowa Huta as a Space of Culture

In the past two decades, Nowa Huta has begun to be rediscovered—first by researchers and urban planners, later by tourists and creators. It has been recognized that its unique urban layout, architectural scale, and rich history constitute cultural capital rather than merely a burden of the past.

Cultural institutions such as the Nowa Huta Cultural Centre, the Ludowy Theatre, and the Museum of Nowa Huta play a significant role. Festivals, exhibitions, workshops, and community events take place here, linking historical memory with forward-looking thinking about the district. Grassroots projects are also developing dynamically: neighborhood clubs, community initiatives, murals, and artistic activities in public space.

One particularly interesting phenomenon is post-industrial tourism. More and more people visit Nowa Huta to see the original 1950s housing estates, the former steelworks complex, or modernist architecture from later decades. Importantly, the narrative about the past is becoming increasingly polyphonic: alongside pride in industrial heritage, there is growing reflection on the social and environmental costs of this history.

The Nowa Huta of the Future – Challenges and Opportunities

Contemporary Nowa Huta faces a number of challenges. The aging of buildings and residents, industrial transformation, and the need to modernize infrastructure all require a long-term strategy. At the same time, the district has enormous potential: extensive green areas, a cohesive urban layout, and an increasingly strong local identity.

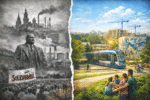

More and more often, Nowa Huta is spoken of as a space for green transformation and social innovation. Revitalization of squares, parks, and boulevards; development of public transport and cycling routes; programs supporting local businesses and culture—these are only some of the directions of change. Crucially, the character of the place must be preserved: modernization cannot mean erasing history.

Nowa Huta has a chance to become a model example of a district that does not feel ashamed of its past but interprets it creatively. Instead of being merely a “bedroom district,” it can become a space of encounter, dialogue, and shared responsibility for the common future.

Nowa Huta remains one of the most intriguing urban phenomena in Poland. Born as an ideological project, it survived systemic change and entered the 21st century carrying the burden of a difficult yet fascinating history. Today it is increasingly clear that what was once a symbol of the past can become an inspiration for the future—for thinking about the city as a community, about space as a public good, and about history as a source of identity.

Nowa Huta is no longer just a “monument to the communist era.” It is a living organism that is changing, maturing, and redefining itself. And its future—like the future of all cities—depends on the dialogue between memory and modernity, between the needs of residents and the visions of urban planners, between everyday life and the dream of a better space to live.