The Centennial Hall (Jahrhunderthalle in German), located in the heart of Wrocław, is one of the most significant architectural monuments of the 20th century in Poland and Europe. Designed by the visionary architect Max Berg, it was completed in 1913 as a monumental exhibition space built to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the victory over Napoleon at the Battle of Leipzig.

Today, it stands not only as a symbol of Wrocław but also as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Although its massive silhouette is familiar to nearly every resident of the city, few know all the secrets hidden within this remarkable structure.

Here are 10 secrets of the Centennial Hall that reveal not only its extraordinary history but also the genius of engineering and the spirit of the era in which it was created.

1. A Concrete Wonder of Its Time

When the Centennial Hall was built, reinforced concrete was still a relatively new material. Max Berg boldly decided to construct the entire building from reinforced concrete — without the use of traditional steel supports. The result was a dome with a diameter of 65 meters — the largest of its kind in the world at the time of its completion.

For comparison, the dome of St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome measures only 42 meters. Berg’s daring vision made the Centennial Hall a pioneering feat of engineering that opened a new chapter in the history of concrete architecture.

2. Inspired by the Pantheon… and a Pigeon Loft

Berg drew inspiration from classical architecture, particularly the Roman Pantheon, but aimed to create something far more modern — a “temple of technology and progress.” Interestingly, he once joked that his dome resembled a gigantic pigeon loft. In fact, the structure contains numerous ventilation holes and skylights that, in earlier decades, did attract real pigeons.

3. The Hidden Symbolism of the Number Four

The entire design of the Hall is based on the motif of the number four, symbolizing perfection and balance. The dome rests on four main pillars, the building has four entrances, and its interior space is divided into four sectors. At the time of its creation, this was seen as a metaphor for harmony between art, science, religion, and technology.

4. Pioneering Acoustics

The Centennial Hall was one of the first buildings in Europe to feature intentionally designed acoustics for large-scale events. The curvature of the dome and the arrangement of concrete panels were planned to ensure even sound distribution. Modern acoustic engineers still study this achievement, and concerts or multimedia shows held here prove that Berg had a remarkable understanding of the physics of sound.

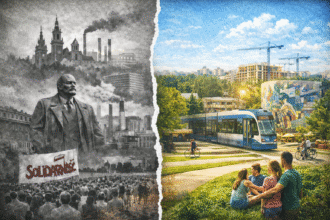

5. Nazi Rallies and Propaganda

In the 1930s, the Hall — then renamed the Volkshalle (“People’s Hall”) — became the site of Nazi rallies. In 1938, it hosted a major NSDAP congress for the Lower Silesia region. Its monumental, austere architecture fit perfectly with the aesthetics of totalitarian propaganda. After World War II, the communist authorities carefully erased traces of this dark chapter of history.

6. The Record-Breaking Screen and Water Show

In 1948, during the Exhibition of the Recovered Territories, the Hall featured one of the largest projection screens in the world — measuring 1,200 square meters. It was accompanied by the now-famous Multimedia Fountain, which, after reconstruction, continues to delight visitors today. The “light, water, and sound” shows at Pergola remain a modern echo of postwar multimedia spectacles once held in the Hall.

7. The Mysterious Tunnels Beneath the Hall

Beneath the Centennial Hall lies a network of underground tunnels and technical chambers. Some were used for transporting exhibition materials, others for storage or maintenance. Legend has it that during World War II, the Germans used these tunnels to hide looted works of art. Although no conclusive evidence has ever been found, many of these tunnels remain closed to the public, adding to the aura of mystery.

8. A Dome Built Without Scaffolding? Almost!

During construction in 1912, Berg and engineer Richard Plüddemann used an innovative method of pouring concrete onto wooden molds that were gradually removed, allowing the structure to “grow” self-supporting. At the time, architectural journals wrote of a “dome built without scaffolding” — not entirely true, but still a testament to the groundbreaking construction methods employed.

9. A Meeting Place of Cultures and Eras

After the war, the Centennial Hall became a venue for countless cultural, sporting, and political events. From concerts by the Rolling Stones and Tadeusz Nalepa, to basketball matches and scientific congresses — the Hall continuously reinvented itself. In 1997, during the Eucharistic Congress, Pope John Paul II celebrated Mass here, marking a deeply significant moment in Poland’s modern history.

10. The Secret of Global Recognition

In 2006, the Centennial Hall was inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List. It was recognized as a revolutionary work of modernism that unites functionality, aesthetics, and visionary structural design. For many residents of Wrocław, this was a moment of pride — a symbolic restoration of a building that had survived wars, ideologies, and social transformations to its rightful place in world culture.

The Centennial Hall is more than just a monument — it is a testament to human imagination, courage, and the passion to create. Its concrete arches tell the story of changing epochs, and every detail reminds us that the true value of architecture lies not only in its walls but in the ideas those walls embody.

Today, the Hall continues to live a new life — as a venue for concerts, exhibitions, and international events — while inspiring architects, engineers, and artists from all over the world.

To understand its secrets is to realize that innovation and heritage can coexist — and that great architecture is timeless.